Memory Experience Loop

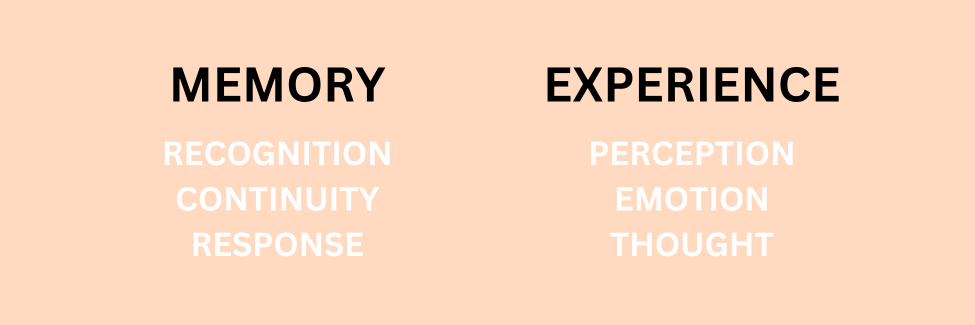

Memory is not a record of what has passed, but a latent potential — the implicit structure that enables recognition, continuity, and response. It allows information structures to link present experience to prior states (recognition), maintain coherence through time (continuity), and adapt through action or perception (response) (Squire & Wixted, 2011; Locke, 1690; Friston, 2010). This interaction, where memory gives rise to experience, produces what has long been called awareness — though the term carries interpretive weight. Here, we refer to it simply as conscious experience. It is not something possessed by a subject but the very process of interaction itself.

Experience, by contrast, is the realization of this potential — the momentary activation of latent memory in the present. Every perception, emotion, or thought is memory expressing itself as event and form. What appears as change is memory unfolding through time; what appears as stability is memory maintaining coherence across time.

This ongoing interplay — memory realizing itself as experience and experience feeding back into memory — forms a continuous loop. It is within this loop that conscious experience arises. We avoid the term awareness due to its conceptual ambiguity; here, conscious experience refers simply to the interactive process itself, not something possessed by a subject but the very unfolding of potential into presence.

Through this lens, memory and experience are not sequential phenomena but complementary aspects of one dynamic system: memory provides the structure; experience reveals it. Their interaction constitutes the basis of all knowing and all feeling — the architecture of life as it is lived.

Which Comes First: Memory or Experience

The relationship between memory and experience has long invited the question of priority: does experience give rise to memory, or does memory make experience possible?

From an empirical perspective, thinkers such as John Locke (1690) and David Hume (1739) argued that the mind begins as a blank slate, acquiring knowledge through sensory impressions that later form memory. In this view, experience precedes memory — perception and repetition give rise to retention and association.

Yet findings in neuroscience and evolutionary biology suggest the opposite. Organisms are born with deeply structured patterns of responsiveness, encoded within the nervous system and genome (Edelman, 1987; Kandel, 2006; LeDoux, 1996). Even at birth, an infant demonstrates reflexes, perceptual preferences, and affective responses that arise without prior learning. These are expressions of inherited information structures — latent memory accumulated through evolutionary continuity.

In this ontological sense, memory comes first. It is the precondition for experience, the structure that enables sensing and interpretation. Experience does not create memory from nothing; it activates what is already potential within it. The cry of the newborn is not learned — it is memory expressing itself as experience in time.

Phenomenologically, however, memory and experience are inseparable. What we call “experience” is memory unfolding through sequence, and what we call “memory” is experience stabilized as potential. Each moment of perception is both the realization of prior structure and the seeding of new potential.

How the Combination Gives Rise to Conscious Experience

If memory is latent potential and experience its unfolding in time, then conscious experience arises from their interaction — from the continuous translation of stored possibility into perceptual actuality.

This translation depends on sequencing — the ordering of activation that gives form to continuity, and thus to the perception of time. Each moment of experience emerges from the partial activation of stored information and simultaneously modifies the structure it arose from. Memory informs the present; the present, in turn, reshapes memory. Conscious experience is this ongoing reciprocity — the feedback between potential and expression.

Neuroscientifically, this dynamic reflects the brain’s predictive architecture. The brain does not passively register stimuli but continuously generates predictions — models derived from prior information — to interpret incoming signals (Friston, 2010; Clark, 2013). What we experience as perception is the reconciliation between prediction (memory) and sensory input (immediate experience). When alignment occurs, we perceive stability; when misalignment arises, we perceive novelty, error, or surprise.

In this model, consciousness is not a substance or localized faculty but the emergent property of this recursive loop. It is the moment-by-moment updating of the system’s internal model of reality — memory becoming experience, and experience refining memory. The so-called “subject” is simply the continuity sustained by this process.

Thus, conscious experience is not produced by a thinker or an observer; it is the interaction itself — the ongoing negotiation between potential and actuality. It is memory realizing itself as the world in motion.

I am going to have to stop here. Anything I say more than this is only going to answer the question of how and why, which is a question that is born out of existing knowledge that has been accumulated not from direct experience.

If you stick to this very basic model (yes, this is also a concept) and begin to see through the layers of identity with integrity, your direct experience will give you the same knowledge.

I will continue the next chapter after I have built Velera. Maybe, even write a book.

References

Locke, J. (1690). An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138.

Squire, L. R., & Wixted, J. T. (2011). The cognitive neuroscience of human memory since H.M. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 34, 259–288.

Which comes first

Hume, D. (1739). A Treatise of Human Nature.

Edelman, G. M. (1987). Neural Darwinism: The Theory of Neuronal Group Selection.

LeDoux, J. (1996). The Emotional Brain.

Kandel, E. R. (2006). In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind.

Clark, A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(3), 181–204.